Meet the Republican building a McCain model on foreign policy

Sen. Todd Young's partnerships with Democrats have helped position him as the go-to Republican to forge bipartisan consensus on global affairs.

While Todd Young was working hard to deny Chuck Schumer the Senate majority, he was privately plotting a massive foreign-policy undertaking with the New York Democrat — one that they hatched in the Senate gym.

Already, a “very enthused” Schumer is vowing to take up and pass the bill he and the Indiana Republican envisioned during their workout sessions, an unprecedented bipartisan measure to counter the technological influence of a rising China that’s dubbed the Endless Frontier Act.

Young came up short in his role as chairman of the Senate GOP campaign arm during the 2020 election cycle, losing the majority. But his frequent partnerships with Democrats and his willingness to challenge former President Donald Trump’s approach to foreign policy have helped position him as the go-to Republican to forge bipartisan consensus on global affairs, which lawmakers say is sorely needed to restore U.S. leadership and confront emerging long-term threats like Beijing.

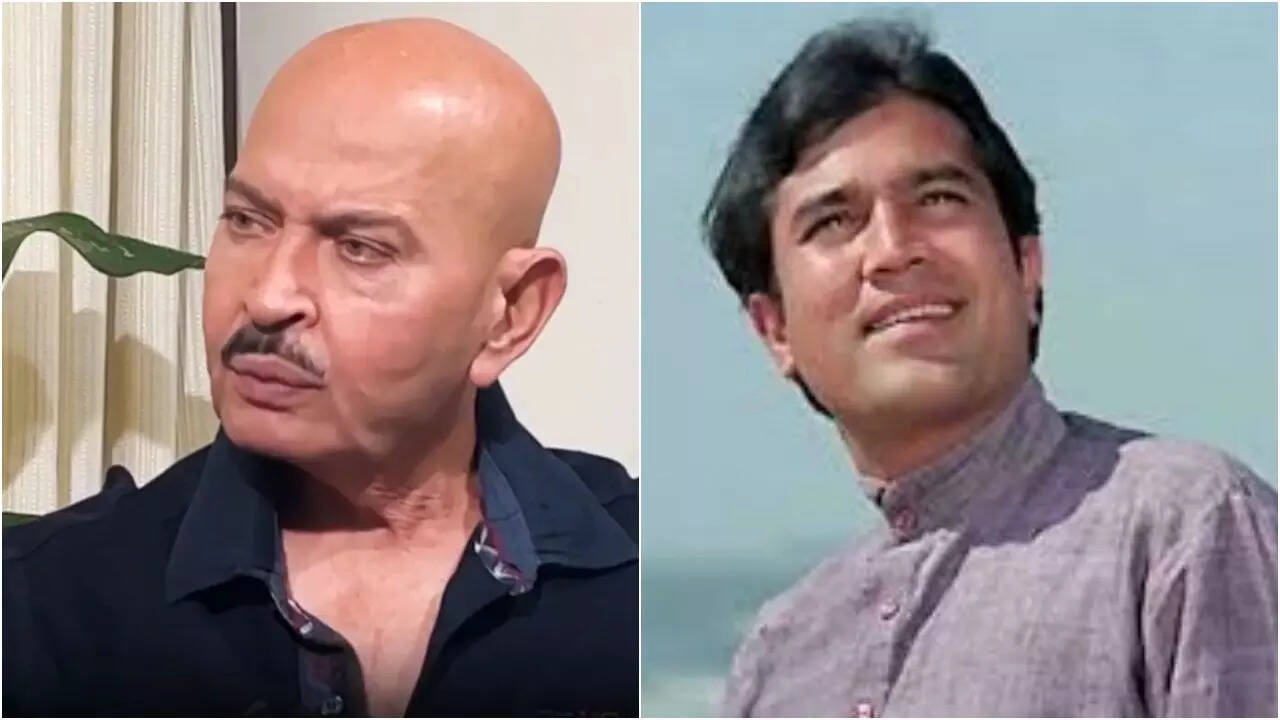

A 48-year-old former Marine officer with the accompanying no-nonsense demeanor, Young has bucked his party’s long-held visions on foreign policy even when it’s politically thorny. But his Trump-era readiness to shake off GOP orthodoxy might look easy compared with the blowback he could face for extending a hand to an opposing party in complete control of Washington, as he prepares to face voters again in 2022.

Young is “laser-focused on policy and he's willing to take risks,” said Sen. Chris Murphy (D-Conn.), one of his closest friends in the Senate and a frequent partner on foreign policy issues. “He doesn’t spend a ton of time worrying about the political ramifications of wading in.”

His approach is reminiscent of that of the late Sen. John McCain, a fellow U.S. Naval Academy graduate who became known as the Senate’s “maverick” for his deep aversion to political expediency and his eagerness to work across the aisle to reach a consensus or strike a deal.

Young, who served three terms in the House before winning his Senate seat, dismisses the idea that voters back home would frown upon his efforts. Projecting a united front on the global stage is “both in the national interest and it comports with the desires and expectations of all of our constituents,” he said in a lengthy interview this week, adding that voters “want foreign policy to be a nonpartisan exercise.”

He also didn’t shrink from praise for Schumer while describing their China partnership, noting that the Brooklynite is “known for being politically shrewd and perceptive.”

“I think the signaling of having the Democratic leader and the chairman of the Republican Senate campaign effort nationally working together is fairly powerful, and he no doubt recognized that,” Young said.

The first-term GOP senator has used his leverage sparingly, and often with success.

During his first year in office, Young blocked a Trump State Department nominee as he pushed the administration to end Saudi Arabia’s blockade of humanitarian aid in Yemen, where the U.S. was assisting the Saudi-led coalition against Iranian proxies. His effort was successful; Riyadh lifted the blockade days later.

He has also partnered with Democrats to rein in presidential war powers — most recently re-introducing his bill with Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) to scrap outdated laws that authorized U.S. military operations in Iraq.

Under Trump, few Republicans spoke out as the commander-in-chief used decades-old war authorizations to legally justify the continued use of military force in the Middle East. Now, after Biden launched retaliatory strikes in Syria last month, lawmakers are renewing their push to yank the old authorizations and craft new ones that are more closely aligned with U.S. interests. The White House recently endorsed the effort, making Biden the first president in modern times to support paring back his own war-making authority.

“It was more challenging to find partners on my own side of the aisle because one doesn’t — this senator included — want to be seen as undermining one’s own administration,” Young said of the Trump presidency, lamenting that foreign policy can often be “a partisan exercise where the party out of power wants to constrain the other.”

Young’s efforts have put him in a powerful position as a bridge-builder under a Democratic president who, despite naming the pandemic as priority No. 1, is facing multiple international conflagrations that have sparked congressional interest. Less than two months into his presidency, Biden has already confronted a coup in Myanmar, an emboldened Iran and long-term challenges with China, among other issues.

As his administration digs in globally, Biden has indicated a readiness to restore Congress’ historical role in crafting U.S. foreign policy. That’s where Young comes in.

“We have, uniquely, a president of the United States who was once chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee,” Young said. “He has a very open and public and quite extensive record of wanting to reform the war powers laws that we have and our practices, and of maintaining senatorial prerogative.”

It wasn’t that easy under Trump.

Young routinely felt like he was “battling” members of the Trump administration, including one-time Secretary of State Rex Tillerson. Those disagreements were most pronounced on the issue of Yemen, where a bloody civil war has torn the country apart and allowed Iran to gain a foothold.

Facing backlash from Young and other lawmakers for his unwavering support for Saudi interests in the region, Trump instead doubled down on that strategy in Yemen, where the Saudi-led coalition in 2017 was blocking humanitarian aid from flowing into the country. Depriving non-combatants of food and medicine, Young argued, would backfire on the U.S. by further destabilizing Yemen in a way that could allow terror groups like ISIS and al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula to thrive.

Tillerson and then-Defense Secretary James Mattis, Young said, “saw this incorrectly in the early stages.”

Young was an outlier among Republicans, most of whom supported the Trump administration’s alignment with the Saudis and its broader attempt to use the Yemen crisis to counter Iran. But as Yemen plunged further into violence, Young saw Iran’s influence there expanding.

So the Republican held up Trump’s nominee to be the top legal adviser at the State Department. He relented when the White House successfully nudged Riyadh to lift the humanitarian blockade.

“I felt as though my head was being patted, and I don’t like that as a U.S. senator,” Young recalled of his standoff with the Trump administration. “So I decided to use my prerogatives as a senator, all the tools in the toolkit. They showed some flexibility ... and I gave them their attorney.”

Murphy described the moment as evidence that Young picks his spots to exert his power — both inside the Capitol and through his frequent conversations with officials from allied nations in the Gulf.

“He’s very good at thinking of ways to use legislation and letters as a means to push players inside Washington, outside Washington, into action,” Murphy said, crediting Young with helping to lift the humanitarian blockade.

Sen. Brian Schatz (D-Hawaii), who is putting together democracy reform legislation with Young, called his counterpart an “unreconstructed conservative” who's young but also “kind of old-school, in the sense of trying to find common ground.”

Young’s profile on foreign policy, in that sense, resembles the reputation that another Democratic colleague on the Foreign Relations panel — Sen. Chris Coons — has developed as an honest broker across the aisle. Coons has lately become a Senate ambassador of sorts for his friend and fellow Delawarean Biden, but it will be harder for Young to fully step into that role for the GOP.

That’s because as often as lawmakers assert that consensus-building on foreign policy displays a vital united front to the rest of the world, bipartisanship isn’t easy to come by in today’s political environment. Not to mention that Young’s partnerships with Democrats shouldn’t be mistaken for cracks in his conservative mantle: He fought hard against his Democratic foreign-policy allies to ensure the GOP kept the Senate.

Now that Young faces re-election in reliably-red Indiana next year, Schatz quipped, “I hope my compliments don’t hurt him in his home state.”

citynews

citynews